Pettengill: The Civil War’s Only Hammerless Revolver

Forum Information

You will earn 1.5 pts. per new post (reply) in this forum.

**Registered members may reply to any topic in this forum**

You will earn 1.5 pts. per new post (reply) in this forum.

**Registered members may reply to any topic in this forum**

-

NHGF [Feed]

- Posts: 17274

- Joined: Mon Oct 30, 2017 5:16 pm

- Contact:

- Status: Offline

Pettengill revolver actions were easily gummed up by blackpowder residue. (Rock Island Auction Co)U.S.A. –-(AmmoLand.com)- Countless revolver variations found their way into the hands of soldiers, both North and South, during the Civil War. From the diminutive Smith & Wesson Model 1 to the heavy-handed LeMat and everything in between, they all looked very similar to one another. That’s what makes the revolvers designed by Charles S. Pettengill so unique. In an era dominated by single-action revolvers with external hammers, the New Haven-based inventor created a double-action revolver with an internal hammer. Sure, there were other double-action models available (like those patented by Starr in 1860), but none of the others were what we would today call “hammerless.” Pettengill designed a few different varieties of his guns. First, in the late 1850s, was the Pocket Model, a .31 caliber design of which just 425 were made across all three variations. Shortly thereafter, the Navy or Belt Model emerged, chambered in .34 caliber; approximately 900 were made. Then came the most well-known variant: the Army Model. This larger model was chambered for .44 caliber round balls and featured a six-shot unfluted cylinder and a 7.5” octagon barrel. The hammerless design, coupled with an equally unique grip frame shape, made for a three-pound revolver with no rival. The patent and production of the guns were equally unconventional. Mr. Pettengill secured the initial patent on July 22, 1856. Then, Charles Robitaille and Edward A. Raymond of Brooklyn received patents for improvements on the design on July 27, 1858. Their improvements streamlined the internal double-action mechanism by reducing the number of parts contained within and having the remaining parts pull double-duty, thereby eliminating the hinged cylinder locking pin of Pettengill’s design. While all three men’s names are found on the revolvers in one way or another, none of them actually produced the guns. Instead, the firm of Rogers, Spencer & Co. of Willowvale, New York, made the revolvers. Located not far from Utica, this company consisted of Amos Rogers and Julius Spencer, as well as Lewis Laurance and George C. Tallman rounding out the “& Co.” portion. Despite all of these people’s involvement in the actual manufacturing of the guns, none of their names are to be found anywhere on them. The existence of Pettengill’s Army Model design owes everything to Amos Rogers, and not just because his company made the guns. It was with Rogers’ help that a trip to see Secretary of War Simon Cameron on December 15, 1861, resulted in the Chief of Ordnance James W. Ripley being instructed to order 5,000 of the unique Pettengill Army Model revolvers at a price of $20 each. Unfortunately, the guns did not fare well in their initial contract sample tests. Like many other blackpowder revolvers, they fouled quickly with blackpowder residue. This gummed up the inner workings and prevented them from cycling properly. With a single-action model, one might be able to overcome this cycling issue by exerting some elbow grease on the external hammer and forcing it to cycle. Because Pettengill’s design had no external hammer, this was not an option. Once the action ceased up, the gun would have to be taken apart to clean it and get it up and running again. Instead of canceling the contract outright – which would have ruined Rogers, Spencer & Co. – more political wrangling saved it by reducing the number of guns requested from 5,000 to 2,000 in June 1862. This allowed the firm to at least attempt to recoup some of their $25,000 spent in tooling to make the guns. The individual price remained at $20 and they were delivered between October 1862 and January 1863, but the cycling issues were never resolved. As a result, more than 15% of the guns delivered were rejected by government inspectors.

Pettengill revolver actions were easily gummed up by blackpowder residue. (Rock Island Auction Co)U.S.A. –-(AmmoLand.com)- Countless revolver variations found their way into the hands of soldiers, both North and South, during the Civil War. From the diminutive Smith & Wesson Model 1 to the heavy-handed LeMat and everything in between, they all looked very similar to one another. That’s what makes the revolvers designed by Charles S. Pettengill so unique. In an era dominated by single-action revolvers with external hammers, the New Haven-based inventor created a double-action revolver with an internal hammer. Sure, there were other double-action models available (like those patented by Starr in 1860), but none of the others were what we would today call “hammerless.” Pettengill designed a few different varieties of his guns. First, in the late 1850s, was the Pocket Model, a .31 caliber design of which just 425 were made across all three variations. Shortly thereafter, the Navy or Belt Model emerged, chambered in .34 caliber; approximately 900 were made. Then came the most well-known variant: the Army Model. This larger model was chambered for .44 caliber round balls and featured a six-shot unfluted cylinder and a 7.5” octagon barrel. The hammerless design, coupled with an equally unique grip frame shape, made for a three-pound revolver with no rival. The patent and production of the guns were equally unconventional. Mr. Pettengill secured the initial patent on July 22, 1856. Then, Charles Robitaille and Edward A. Raymond of Brooklyn received patents for improvements on the design on July 27, 1858. Their improvements streamlined the internal double-action mechanism by reducing the number of parts contained within and having the remaining parts pull double-duty, thereby eliminating the hinged cylinder locking pin of Pettengill’s design. While all three men’s names are found on the revolvers in one way or another, none of them actually produced the guns. Instead, the firm of Rogers, Spencer & Co. of Willowvale, New York, made the revolvers. Located not far from Utica, this company consisted of Amos Rogers and Julius Spencer, as well as Lewis Laurance and George C. Tallman rounding out the “& Co.” portion. Despite all of these people’s involvement in the actual manufacturing of the guns, none of their names are to be found anywhere on them. The existence of Pettengill’s Army Model design owes everything to Amos Rogers, and not just because his company made the guns. It was with Rogers’ help that a trip to see Secretary of War Simon Cameron on December 15, 1861, resulted in the Chief of Ordnance James W. Ripley being instructed to order 5,000 of the unique Pettengill Army Model revolvers at a price of $20 each. Unfortunately, the guns did not fare well in their initial contract sample tests. Like many other blackpowder revolvers, they fouled quickly with blackpowder residue. This gummed up the inner workings and prevented them from cycling properly. With a single-action model, one might be able to overcome this cycling issue by exerting some elbow grease on the external hammer and forcing it to cycle. Because Pettengill’s design had no external hammer, this was not an option. Once the action ceased up, the gun would have to be taken apart to clean it and get it up and running again. Instead of canceling the contract outright – which would have ruined Rogers, Spencer & Co. – more political wrangling saved it by reducing the number of guns requested from 5,000 to 2,000 in June 1862. This allowed the firm to at least attempt to recoup some of their $25,000 spent in tooling to make the guns. The individual price remained at $20 and they were delivered between October 1862 and January 1863, but the cycling issues were never resolved. As a result, more than 15% of the guns delivered were rejected by government inspectors.  When new, the government spent $20 per revolver. They were later sold as surplus for just 27 cents. (Rock Island Auction Co)At least six different units were issued Pettengill guns, with the 3rd Michigan Cavalry receiving 500 guns or one-quarter of the entire contract production. Other units from Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri received the rest of them. Within a year of the Pettengill’s delivery and adoption by the US military, almost all of the revolvers had been removed from service. The government held onto the sub-par pistols for more than a decade before selling them as surplus at a tremendous loss. On October 25, 1876, 196 Pettengills were sold by the St. Louis Arsenal for $1.75 each; in July 1882, another 525 were sold by the New York Arsenal for just 27 cents each. All told, approximately 3,400 Pettengill Army Model revolvers were made. Once the contract was completed, production of Pettengill’s design continued briefly for the commercial market, and the same tooling was used to make the Rogers & Spencer revolver. This reuse of machinery, designs, and parts were because the firm hadn’t yet recouped all of the money they had initially spent to get the Pettengill revolvers into production. The Rogers & Spencer revolver received a government contract for 5,000 guns in November 1864, but only 1,500 were produced before the war ended in April 1865. None were ever issued to troops and they faced the same fate as the Pettengill, as almost all of them were sold as surplus in 1901. Even though Pettengill’s revolver failed to make a lasting impression, it is still important to the story of arms development. His hammerless design was a good idea and would go on to be refined and improved upon by other arms makers. It was the spirit of his patent and the improvements by Robitaille and Raymond that contributed to the hammerless revolvers we have today. The impact of Pettengill’s patents have been far-reaching. Aspects of his safety and locking mechanisms have been cited by D. B. Wesson and John Moses Browning in subsequent patents in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and other citations have come as recently as the 1980s by Heckler & Koch. Pettengill’s design was ahead of its time. Perhaps if it had been produced a few decades later after the advent of smokeless powder, which was less prone to quick fouling, it might have been a success. Alas, this is just one of many “what ifs” in the realm of history.

When new, the government spent $20 per revolver. They were later sold as surplus for just 27 cents. (Rock Island Auction Co)At least six different units were issued Pettengill guns, with the 3rd Michigan Cavalry receiving 500 guns or one-quarter of the entire contract production. Other units from Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri received the rest of them. Within a year of the Pettengill’s delivery and adoption by the US military, almost all of the revolvers had been removed from service. The government held onto the sub-par pistols for more than a decade before selling them as surplus at a tremendous loss. On October 25, 1876, 196 Pettengills were sold by the St. Louis Arsenal for $1.75 each; in July 1882, another 525 were sold by the New York Arsenal for just 27 cents each. All told, approximately 3,400 Pettengill Army Model revolvers were made. Once the contract was completed, production of Pettengill’s design continued briefly for the commercial market, and the same tooling was used to make the Rogers & Spencer revolver. This reuse of machinery, designs, and parts were because the firm hadn’t yet recouped all of the money they had initially spent to get the Pettengill revolvers into production. The Rogers & Spencer revolver received a government contract for 5,000 guns in November 1864, but only 1,500 were produced before the war ended in April 1865. None were ever issued to troops and they faced the same fate as the Pettengill, as almost all of them were sold as surplus in 1901. Even though Pettengill’s revolver failed to make a lasting impression, it is still important to the story of arms development. His hammerless design was a good idea and would go on to be refined and improved upon by other arms makers. It was the spirit of his patent and the improvements by Robitaille and Raymond that contributed to the hammerless revolvers we have today. The impact of Pettengill’s patents have been far-reaching. Aspects of his safety and locking mechanisms have been cited by D. B. Wesson and John Moses Browning in subsequent patents in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, and other citations have come as recently as the 1980s by Heckler & Koch. Pettengill’s design was ahead of its time. Perhaps if it had been produced a few decades later after the advent of smokeless powder, which was less prone to quick fouling, it might have been a success. Alas, this is just one of many “what ifs” in the realm of history.  Script NW for Nathaniel Whiting, a sub-inspector for arms contracts. (Rock Island Auction Co)More than a century and a half later, Pettengill’s failure to launch has turned out to be a good thing for some people. Because so few were made and even fewer survive, they are highly sought after today by gun collectors. Standard guns made for the civilian market after the fulfillment of the government contract can cost more than $1,000.

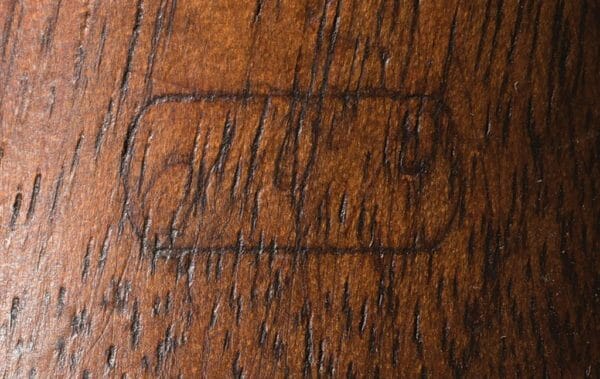

Script NW for Nathaniel Whiting, a sub-inspector for arms contracts. (Rock Island Auction Co)More than a century and a half later, Pettengill’s failure to launch has turned out to be a good thing for some people. Because so few were made and even fewer survive, they are highly sought after today by gun collectors. Standard guns made for the civilian market after the fulfillment of the government contract can cost more than $1,000.  Inspection marks on metal parts from Nathaniel Whiting and Giles Porter. (Rock Island Auction Co)Guns found with military inspector markings on the grips and assorted metal parts are worth even more. The grips will be marked with a script NW for Nathaniel Whiting, one of many sub-inspectors for arms contracts. His last initial is often found stamped twice on metal components and can sometimes be accompanied by a P, which is the mark of another sub-inspector by the name of Giles Porter. It’s not uncommon to see martially marked examples in fair condition selling for $5,000 – $10,000, and those in exceptionally good condition have gone as high as $20,000.

Inspection marks on metal parts from Nathaniel Whiting and Giles Porter. (Rock Island Auction Co)Guns found with military inspector markings on the grips and assorted metal parts are worth even more. The grips will be marked with a script NW for Nathaniel Whiting, one of many sub-inspectors for arms contracts. His last initial is often found stamped twice on metal components and can sometimes be accompanied by a P, which is the mark of another sub-inspector by the name of Giles Porter. It’s not uncommon to see martially marked examples in fair condition selling for $5,000 – $10,000, and those in exceptionally good condition have gone as high as $20,000. About Logan Metesh Logan Metesh is a historian with a focus on firearms history and development. He runs High Caliber History LLC and has more than a decade of experience working for the Smithsonian Institution, the National Park Service, and the NRA Museums. His ability to present history and research in an engaging manner has made him a sought after consultant, writer, and museum professional. The ease with which he can recall obscure historical facts and figures makes him very good at Jeopardy!, but exceptionally bad at geometry.